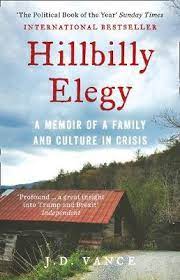

J.D. Vance became famous -- bankable -- after publication of

Hillbilly Elegy in 2016. Seems like everybody was reading it back then. Many praised the beauty of the writing. Others actively hated it.

All the regional Appalachian activists I know, and the academics teaching or writing in the large field of "Appalachian Studies," spat nails about it. Still do. They told me in many conversations that Vance's autobiography about growing up poor and "Appalachian" in Ohio presented the grossest of generalizations about a culture built to sink without protest into despair. When the movie version came out in 2020, directed by Ron Howard, the push-back against Vance's generalizations about Appalachian culture grew even shriller.

I confess that I never read the book and I avoided the Netflix film. I took my friends' word for it (always a dangerous proposition, but hey! I'm busy). No matter how vibrantly, sharply written, no matter how perfectly scripted for the Hollywood treatment, Vance's version of reality has outlasted its shelf-life.

So I'm primed to sneer a little at J.D. Vance, especially after he became a vocal Trumpist and declared he was running to replace Rob Portman in the US Senate from Ohio, financed in large part by libertarian billionaire Peter Thiel. I

wrote disapprovingly last March about how Thiel, a kind of cultural snarling dog, really, was trying to buy Vance a Senate seat with $10 million. Meanwhile, Vance the cherub-cheeked pudge of a new author of 2016 (who looked like this back then)...

is now campaigning for the US Senate as a different sort of avatar -- angry-guy Trumpist J.D. Vance:

That change in persona -- from a Harvard-educated intellectual who "came across as guileless, boyish" -- to "playing Don Jr. on the Internet" -- that transformation becomes major grist for an amazing piece of in-depth analysis by Simon van Zuylen-Wood in yesterday's Washington Post, "

The Radicalization of J.D. Vance."

Let’s start with the beard. J.D. Vance didn’t used to have one. The Vance who in 2016 achieved incandescent literary fame with his memoir “Hillbilly Elegy” was all baby fat and rounded edges. The Vance I’m watching now, from the back of a coffee shop in the depressed steel town of Steubenville, Ohio, has covered up his softer side.

One of Vance's friends told van Zuylen-Wood that the change in Vance was more than just outward appearance: “He’s going for a kind of severe masculinism thing. He looks like Donald Trump Jr.” Van Zuylen-Wood followed Vance on the campaign trail and verified the attempt to portray a bullying masculinity, though it often looked inauthentic: "Watching Vance campaign, I felt him straining to deliver his talking points in an angry register." Plus Vance's "shit-posting" on social media, which is "the signature style of young radicals on the right." Elegant writing be damned when you're trying to impress the Trumpists.

If you need to play to the Trump base — which Vance suddenly, desperately, needs to do — it’s not a bad idea to do so via online trolling: “You can own the libs without going on long paranoid spiels about all your enemies within the Republican Party who have failed to steal the election for you.”

Which leads to the central question behind this long profile: Is Vance a changed or a fraudulent person?

During the 2016 presidential campaign, Vance was known as a never-Trumper, so his cutting remarks about Donald Trump back then are being resurrected now by his Republican primary opponents. "Every campaign stop he makes, he patiently tries to explain away his past Never-Trumpism, which has been exhumed in the form of deleted tweets and Charlie Rose clips. An attack ad playing his anti-Trump sound bites ends with a woman saying, 'That’s the real J.D. Vance.' ”

I could go on grabbing quotes from this delicious article, past anyone's patience for taking it all in, but in answer to whether Vance's transformation amounts to fraud or a genuine change of heart, van Zuylen-Wood writes this hell of a paragraph:

Vance’s new political identity isn’t so much a façade or a reversal as an expression of an alienated worldview that is, in fact, consistent with his life story. And now there’s an ideological home for that worldview: Vance has become one of the leading political avatars of an emergent populist-intellectual persuasion that tacks right on culture and left on economics. Known as national conservatism or sometimes “post-liberalism,” it is — in broad strokes — heavily Catholic, definitely anti-woke, skeptical of big business, nationalist about trade and borders, and flirty with Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orban. In Congress, its presence is minuscule — represented chiefly by Sens. Josh Hawley and Marco Rubio — but on Fox News, it has a champion in Tucker Carlson, on whose show Vance is a regular guest. And while the movement’s philosopher-kings spend a lot of time litigating internal schisms online, the project is animated by a real-life political gambit: that as progressives weaken the Democratic Party with unpopular cultural attitudes, the right can swoop in and pick off multiracial working-class voters.

That's the kind of paragraph that deserves its own long profile. And there's much else in van Zuylen-Wood's reporting, especially on the intellectual underpinings of "national conservatism" (Peter Thielism) that incidentally indict classical liberalism for its own blindnesses and bland assumptions.